|

Egypt, art during Middle Kingdom, Dynasties XI - XIII

(2050 -1786 B.C.)

The reunification of Upper and Lower Egypt is the signal event of the Middle Kingdom. The Theban kings of the era exercised successful bureaucratic control. They were also capable warriors, suppressing the

Bedouins and other Asian invaders.

Limestone relief; sarcophagus Queen Kwit (consort of King Mentuhotep II); ca. 2061-2010 B.C.; Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Mentuhotep II was the king who unified Egypt and ruled for about fifty years. He also revivified the office of Pharaoh, Chancellor and Vizier, which had fallen into disuse during the interegnum.

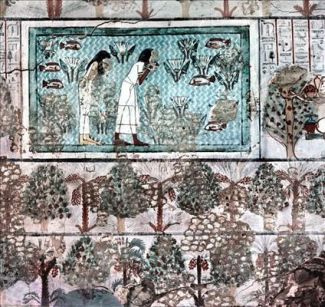

Detail; Tomb ornament, Middle Kingdom, Egypt.

Kings were always identified with the god Horus in Egypt. Mentuhotep assumed a particular manifestation of Horus : He who unified the two lands. For the ancient Egyptians, titles were particularly important.

The word Pharaoh, for instance is really a combination of five names meaning " the big or royal house. " The king was an incarnation of the god Horus.

Horus

The king got a name related to his father's name right after he was born ; later he would get the title " unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt." Other titles such as " Horus of Gold " might follow later. Horus, depicted

as a human with a hawk's head, or sometimes in abbreviated form just as a hawk. His name meant " One far above ." In the Heliopolitan cosmoslogy, the common belief system in ancient Egypt, Horus was thought

to be the offspring of the unions of two of the primary gods : Osiris and Isis.

Small statue of the goddess Isis holding her child Horus; Middle

Kingdom, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

For the Egyptians, the world began with an ocean existing in total darkness. They called the darkness Nun. In this ocean where small pieces of the God Atum. These pieces came together,

first as a spot of heat, then as the sun itself. Atum dried made a small section of Nun and this established the first spit of land. It was here that Atum created the world. The center of Atum worship was the

Sun-religious center, which the Greeks called Heliopolis. The first man and woman-Shu and Tefnut-were the creations of Atum's saliva. Shu and Tefnut gave birth to the gods Geb and Nut, who in turn gave birth

to the gods Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nepththys. This group of gods together was called the Great Ennead by the Greeks, ennead meaning nine.

Necklace with amulets; tomb of Princess Khnemet (ca. 1922 - 1878 B.C.); 17.1 x 35 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Later Horus battled Seth, who had killed Osiris for power over Egypt. Horus lost one of his eyes in this battle. Eventually, the eye came back to him. The returned eye became a symbol of Egyptian safety and good

fortune against impossible odds. After the return of the eye, Horus became the principal god of the living.

With the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt during the Old Kingdom, the capitol became Memphis because it was at the lowest point in the Nile. In addition to the Great Ennead, each locality had its own gods. In

Memphis the local god was Ptah. By the Third Dynasty, a new creation myth known as the Memphis Theology of Creation prevailed. It had a new place for the previously only local god Ptah. In the new cosmology,

Ptah was made out of pure thought and also created thought. In the Memphis version of the creation myth, the earth was created by five gods, not just one. The leader was a rabbit goddess named Unut ; her minions

were baboons with the heads of dogs. The baboon/dogs were sacred to Thoth, one of the other major indigenous gods of Memphis.

History

Written documents such as the "Story of the Eloquent Peasant," "Admonitions of Ipuwer," and the "Song of the Harper," give us some sketchy information about the First Intermediate Period. The extant literature is

a melancholy story of repeated incursions by Asiatic nomads, social chaos, poverty, and famine. The canal system broke down because of the dry conditions.

The first part of the Middle Kingdom took place from 2160-2061 B.C. under Mentuhotpe I, during this First Intermediate Period. This period ended with the war between the King of Herkleopolis and the Theban Prince

Nebhepetre Mentuhotpe II. Mentohotpe II (who ruled ca. 2008 - 1957 B.C.) prevailed and the country was re-unified. Mentuhotep II's tomb is considered by scholars to be one of the most original, as well as highly

technically and aesthetically accomplished. The tomb was carved into the cliffs on the western bank of the Nile, in Thebes at Deir el-Bahri. Mentuhotepe II's reign marks the real start of the Middle Kingdom.

Tomb wall, chapel of Khnumhotep, Beni Hasan; Twelfth Dynasty.

Memphis was the capitol during the Eleventh Dynasty (2061-1785). Mentuhotep II's mortuary temple and tomb are in Thebes at are Deir el-Bahri. We know little about his successors, Mentuhotep III and IV. The slight

evidence we have suggests that theirs was a time increasing trade with Punt, a source of spices and other goods from the tropics. It was also a time of more quarrying (primarily for royal monuments and tombs)

in the Wadi Hammamat, a valley between Koptos and the Red Sea.

Sandstone statue of King Nebhepetra Montuhotep, Eleventh Dynasty; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

The Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1785 B.C.) was founded by Ammenemhet, a vizier under Mentuhotep II, known for his successful expedition under King Mentuhotep IV to Wadi Hammamat. The capitol under Ammenenhat I was moved

closer to Memphis, to Itjry-Tauy from Thebes. Ammenemhet I created a system of forts to protect Egypt from Asian incursions from the Eastern section of the Nile Delta.

Amenemhat I (1991-1962) was assassinated by some his closest advisors. While he had made great strides in pacifying Egypt, the authority of the central government was not completely secure in the nomes (provinces).

The provincial leaders still held enormous power. The kings during the Twelfth Dynasty were called either Ammenemhat or Sesostris. Ammenemhat I's son Sesotris I, was more imperialistic than his father. He took

over Nubia and built many imposing military and religious structures including the White Chapel at Karnak dedicated to the god Amun. This was limestone and small (6.54 x 6.45 m) but exquisitely decorated. It

functioned as a site for religious rituals and storage space for the god Amun's sacred boat.

There is scant historical record on Sesostris I (1962-1928 B.C.), Amenemhat II (1928-1895), or Sesotris II (1895-1878). The Greek historian Herodotus wrote extensively about Sesostris III (1878-1842 B.C.). Sesostris

III was a successful military leader who built more fortifications to protect against two groups-the Kerma proples and the C-group--and Sesostris III secured the southern borders up to the Second cataract of

the Nile. Sesostris III may have built a fort at Kerma, at the Third cataract. These forts also regulated trade and immigration. Herodotus claims that Sesotris III traded with Crete, and extended Egyptian influence

far into western Asia, perhaps as far as northern Greece. Under Sesotris III, the nomarchs were finally pacified, and the central administration substantially strengthened. Sesostris III installed a pair of

viziers, under his direct and sole control, who administered Egypt.

Little is known of Ammenemhat IV (1797-1790) or his rule. Some of the oldest known letters in history date from his era. They are from an official of the Semna fortress at the Second Cataract who talks about trade

with the Nubians and also the dangers of the Nubians.

The final monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty was a woman-Sobekneferu, the daughter of Amenemhat III, who probably died without a living son. This is the first verified female ruler of Egypt, though there is some evidence

that a woman ruled at the end of the Sixth Dynasty. The only statues of Sobekneferu that remain are headless; her tomb has never been found. All we know about Sobokneferu was that her rule lasted nearly four

years, from 1790-1785 B.C.

|