Very Early Roman Empire and it's art (30 B.C.-53 A.D.)

The Roman Republic ended with Julius Caesar’s death on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. Caesar had attempted to use the power of the portrait for political ends and in so doing hastened his downfall. When Caesar issued coins with his own image in 45 B.C.,

he was the first Greek or Roman leader to do so. In the past, images on Roman or Greek coins were only of dead leaders. The practice of putting the image of a live leader on a coin was something done by Asian

kings. This use of his portrait made many Romans nervous about impending monarchy, something they feared. Of course, Caesar had been elected Dictator twice before issuing the coin with his picture. By the time

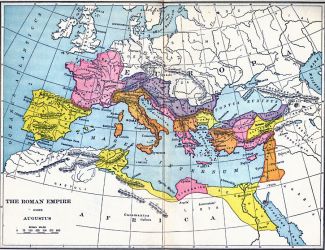

of Caesar, Rome dominated the entire Mediterranean as well as portions of northern Europe.

When Caesar gained control of Rome in 49 B.C. he had plans to make Rome into the new Athens—a center of art and culture. The biographer Suetonius said among the high points of the plans were ″a Temple to Mars, to

be the biggest in the world. To build it he would have to fill in and pave the lake where a mock naval-battle had been staged, and a massive theatre that would slope down from the Tarpeian rock on the Capitoline

Hill.″

Some of Caesar’s plans were carried out by Octavian, his grand-nephew and adopted son. Octavian was also a prolific builder, restorer, and patron of the arts, particularly sculpture. Octavian, M. Antony and M. Lepidus

were recognized as the ruling Triumverite by the Senate in November 43 B.C. When Caesar was declared a god by the Senate, Octavian was recognized as divi filius. Octavian defeated Antony at Actium in

31 B.C., and forced Lepidus into an early retirement. Now Octavian received the title Augustus and effectively controlled the country.

Map of Rome at the time of Augustus

Reliefs and sculpture of the Republican era tended to be realistic. Unlike the Greeks, the Romans of the Republican period tended to depict specific events as they actually occured rather than representing them

through a similar event in mythology or remote history. In the early Empire, however, Romans became aware of their important place in history and wanted to celebrate their own stories, their own mythical figures.

Portion of Frieze from the Ara Pacis [Peace Altar], Rome ; 9 A.D; commemorating Augustus’ successful return from defending the northern and Mediterranean borders. The central figure is the goddess Tellus, Mother Earth. The two children in her arms symbolize the two first residents of Rome Romulus and Remus. The tiny oxen and sheep as well as wheat, flowers, fruit, vessels of wine, all symbolize prosperity. Many of these goods actually came from newly conquered North Africa and Spain. Oxen were used to pull ploughs and carts. The Romans had not yet come up with an effective horse harness.

Public sculpture during the Augustan era also had a propagandistic purpose. Despite his stated intent to restore the Republic, Augustus had actually taken over the government and deprived the Senate of its traditional

power. Augustus’ claim to power rested on his descent from Julius Caesar as well as his military victories. Augustus was eager to show that through Caesar he was related to Aeneas and ultimately the goddess

Venus.

Like Republican statues, those of the early Empire borrowed freely from Greek prototypes. The statue below of Augustus uses the stance and body of a Greek sculpture called the Doryphoros [Spearbearer] created

in about 450 B.C, at the height of Greek artistry. The Roman public, of course, knew that Augustus did not have the body of a Greek god, but putting Augustus’ head on the Doryphorus was a form of identification

with Greek models and a tribute to the Greco-Roman culture.

The Prima Porta, statue of Augustus, 20 A.D. to commemorate his victory over the Parthians (kingdom of Asia Minor and long-time nemesis of the Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians). Currently in Rome. Augustus is shown in the tunic, garb identified strongly with the deified Julius Caesar. In the Republic, the toga was the formal costume of the Roman senator. Much scholarship has focused on the question of why Augustus is depicted barefoot here, extremely unlikely for a general in battle. Many scholars believe he is shown barefoot to identify his status as a god. The cupid to his left is riding a dolphin. Cupid was the son of Venus.

Venus was an Italian goddess of great antiquity. But to Romans of the Republic and Empire, Venus and the Greek goddess Aphrodite were one. As a noun, the word Venus meant charm and beauty. Venus was the

numen (spirit) who made gardens grow. She did not have power over the fertility of animals. Varro, who wrote in the First Century B.C., says that on the festival celebrating Venus, Romans ate

″Venus who has felt Vulcan’s power″ in other words cooked vegetables. In her manifestation Venus Genetrix, she was considered the mother of the imperial family (the Julio-Claudians) and was

therefore prevalent in imperial statuary and reliefs. Most statues of Venus Genetrix are clothed; the statue below is simply a plain-vanilla version of Venus. The statue was probably in the

villa of a wealthy patron.

A noble woman as the goddess Venus, dressing her hair. The diadem identifies her as Venus. Bronze; 9 ½ inches high; ca. First Century A.D. Private collection, Great Britain.

Through Aeneas, the gens (clan) of the Julians claimed that Venus was their ancestor. The Julians included Julius Caesar as well as Augustus. Aeneas was the son of Anchises and Aphrodite. According

to Homer, Aeneas was an officer in the Trojan army who was treated as an equal of the gods. He left Troy with his father and son and wandered around the Mediterranean. In Homer’s Iliad, Aeneas

went to Sicily, and perhaps the Italian peninsula. Other ancient writers associate Aeneas with the founding of the Latin League, though not Rome itself. In Vergil’s Aeneid, Aeneas was much more

closely tied to the actual establishment of Rome.

Because there are so many similar versions of this depiction of Venus, scholars believe there was a Greek statue, now lost, from which they were copied.

Fragment of a marble statue of Venus Genetrix, Roman; ca. First Century A.D.; 15 inches high; private collection, Great Britain. Here the clean, nearly sheer drapery of her garment emulates Greek statues of Aphrodite.

During the Iron Age, the Italians buried their dead; but for other tribes in Italy, cremation was the norm until about the Second Century A.D. The marble container below was meant to hold the ashes of the

deceased. In Greek and Roman literature, the most important thing to do with the dead was to cover them so the gods would not see them. It was thought that the sight of a corpse would offend the gods.

After death, the body was bathed and dressed in clothes the deceased may have worn on special occasions. Family was permitted to grieve, but according to Roman law, screaming, tearing clothes, and other

excess shows of lamentation were forbidden. The funeral pyre also burned funerary gifts, though some were put in the tomb. According to Roman law, no one was allowed to be buried within the city limits

of Rome or any other Roman city.

Roman marble lidded Cinerarium, ca. First Century A.D., 15 x 13 ½ x 10 ½ inches, Private Collection, United States. The image in the center is the deceased. He is surrounded by dolphins with the faces of men.

The female goat in Roman myth suckled the god Jupiter. It was a symbol of fecundity and care. For the Christians, the male goat was a symbol of evil and cunning as well as virile potency. During the Roman

Republic and Empire, it was thought that the goat had its origin on the island Capri, close to Sicily.

Roman marble head of a goat; ca. First Century A.D.; 12 inches high; private collection, Great Britain.

During the late Roman Republic and early Empire, the small-headed horses seen in Etruscan vases started to die out. They were replaced by horses of Persian origin that had bigger heads and were generally

studier. Horses were expensive; they were essential for warfare, racing, and transport. The equites, comparable to the upper middle class, were originally cavalry officers. They were one rung

down from the top of the social classes—the patricians. In order to qualify as an equites, one had to own a horse. In the early Republic there were 300 equites. The equites as a separate ordo had great political power during the Republic, but by the time of the empire, while there were extremely powerful individual equites, they did not hold power as a

distinct group.

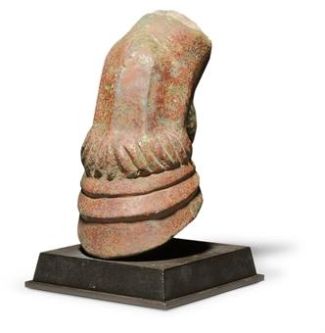

Roman bronze horse hoof, ca. First Century B.C.; 7 ¼ inches high; Private Collection, Great Britain.

The neutral background and floral decorative motifs of the altar to Hercules below follow Greek prototypes for reliefs. The artist chose to show the result of Hercules labors rather than Hercules in action.

In frescoes and reliefs from the early Roman Empire that show animal fights and hunting, humans are generally depicted as disproportionately small relative to the huge beast they are battling. Hunting

was enjoyed by Augustus and other early emperors. Games involving wild beasts (venationes) were particularly popular at this time in Rome. They were held in the morning in the Ludus Matutinus.

Gladiator fights were held in afternoon or evening. By the Third and Fourth Centuries A.D., lions, boars and other wild animals were rare in the area controlled by the Roman Empire.

The cult of Hercules is thought by scholars to be the earliest foreign cult in Rome. No women were admitted to the temples of Hercules, the chief one was at the Ara Maxima. Dogs were also not permitted at

the temples.

Roman altar for burnt offering to Hercules, depicting two of the labors of Hercules: the Erymanthian boar, captured by Hercules, and the skin of the Nemean lion, whom Hercules killed. There were a total of twelve labors of Hercules. ca. First Century A.D.; 34 ½ inches high; Private Collection, United States.

The outfit worn by Melpomene in the piece below is modest, befitting a Roman matron. Only prostitutes wore togas like men. Roman matrons wore tunics made of silk, linen, or cotton. Prostitutes often wore

togas of diaphanous material. The hairstyle of Melpomene is simple and dowdy. At the time, the upswept bangs and tightly drawn-back hair of Livia (who became the wife of Emperor Tiberius Claudius Nero)

were in style.

Roman marble statue of Melpomene, goddess of tragedy, daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne. She is carrying a tragic mask. Ca. First Century A.D.; 27 ½ inches high; Private Collection, United States.

Hercules is identifiable by the skin of the Neman lion, which he wears over his head. The canine teeth of the lion are depicted in a stylized way above his forehead. Augustus and later emperors were often

likened to Hercules. Roman theatres were often at least partially roofed. There was a wall at the back of the stage (scenae frons), which had columns and other areas that were decorated. The

outer walls, which were often square, had columns, also elaborated decorated. This piece may have come from either location in a Roman theatre.

Roman tragic theatre mask of Hercules; ca. First Century A.D. Thought to be an ornamental element from a theatre. 16 3/8 inches high; Private collection, United States.

The god of herdsmen, isolated places, mountains and music, Pan came from Arcadia in Greece. Pan helped the Athenians win wars, so this would have been a somewhat patriotic statue. By the time this statue

was created, the Pax Romana was probably in place. Augustus decided to cease expanding the empire after the loss of three legions at the battle of the Teutoberg Forest (today Lower Saxony, Germany) in

9 A.D.

Worship of Pan came somewhat late in Greek history; there are no shrines to him before the Fifth Century B.C. Pan is typically shown on Greek reliefs with nymphs, flowers, and other flora and fauna common

to pristine forests. The piece below is probably a Roman copy of a Greek relief from the Fourth Century B.C.

Roman marble statue of Pan; ca. First Century A.D.; 16 ¾ inches; Private Collection, United States. Holding his characteristic pedum (shepherd’s staff). The remnant of a leg on the right shows that this was once part of a larger piece. It is believed that the leg probably belongs to a statue of Dionysius.

|